Long ago, a man rang my then newly established radio show and (as people sometimes do) went on and on telling me the rigmarole of his life, without hope or insight, clearly expecting me to be brilliant and sort it all out, the adult version of “kiss and make it better.” He never drew breath and when eventually he paused, I answered the last reiteration of a much repeated question with “No.” End of. I am not a shock jock, I wasn’t trying to score points or be a clever dick. I recognised that either I devoted the whole programme to him or I gave him a response he could kick at – so I did the latter. I only remember doing it once. But when you listen to these stories, layer upon layer of misunderstanding, convention for the sake of it, confusion reinforced by endless social silt and repetition,

and sort it all out, the adult version of “kiss and make it better.” He never drew breath and when eventually he paused, I answered the last reiteration of a much repeated question with “No.” End of. I am not a shock jock, I wasn’t trying to score points or be a clever dick. I recognised that either I devoted the whole programme to him or I gave him a response he could kick at – so I did the latter. I only remember doing it once. But when you listen to these stories, layer upon layer of misunderstanding, convention for the sake of it, confusion reinforced by endless social silt and repetition,  there is little you can do. Learning how little I could do was always chastening. I remember reading in Isaac Bashevis Singer that “it is better to do a little with a good heart than more out of obligation.” I thought so.

there is little you can do. Learning how little I could do was always chastening. I remember reading in Isaac Bashevis Singer that “it is better to do a little with a good heart than more out of obligation.” I thought so.

Of course there are occasions when you say yes and regret it afterwards, just as in other circumstances you decline and wish you hadn’t.  This is not a short course in rectitude. There is no guarantee that learning to say no will mean that you only say it at the right juncture but permitting yourself to say no when you mean it can catch you a psychological breathing space.

This is not a short course in rectitude. There is no guarantee that learning to say no will mean that you only say it at the right juncture but permitting yourself to say no when you mean it can catch you a psychological breathing space.

Although I am aware of the advantages for women alone, the ill, the elderly and so on, I have had a mobile for three months only and I have never missed it. I am cackhanded, use two pairs of specs, hate the sound quality and have a deep antipathy to being removed from focus on the moment. I don’t want to take pictures, play music, message friends on Facebook, tweet or twitter. I have eyes, ears, a memory, a landline and an email: that will do. Oh and an aversion to having to have what everybody else has, just because they do.

Recently I have read quite a lot about social media,  the maladaption of the young to the constant presence of some screen or other. It is as tough to be a good enough parent nowadays as it is to be a healthy enough child. So although I could have done without the latest Google horror story (“… makes millions from the plight of addicts” Sunday Times 07.01.18) , I am not surprised. I do not buy on line. I do not bank on line. I live an older simpler life. I just said “no.”

the maladaption of the young to the constant presence of some screen or other. It is as tough to be a good enough parent nowadays as it is to be a healthy enough child. So although I could have done without the latest Google horror story (“… makes millions from the plight of addicts” Sunday Times 07.01.18) , I am not surprised. I do not buy on line. I do not bank on line. I live an older simpler life. I just said “no.”

It would not occur to me to say no to (small amounts of) dairy: I am not allergic. I am a convinced omnivore, eating fruit and vegetables in every widening variety but don’t start telling me what I shouldn’t eat: I come from 1950s austerity when we were grateful for food we didn’t actively dislike and we learned to cook for taste and nourishment.

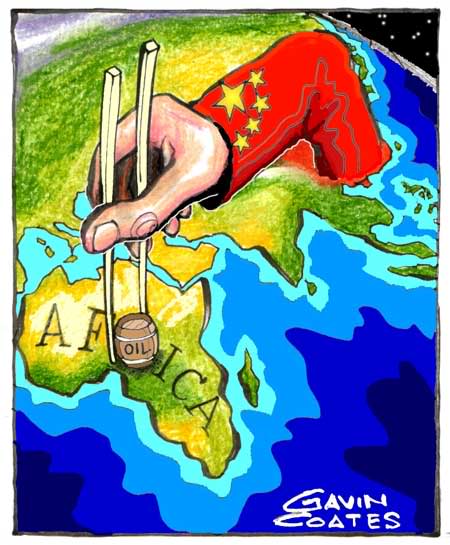

You go to the sales if you like, but surely it must have begun to occur to people that the prices are set artificially high so that they may fall and you go when you go and pay what you pay but the endless lauding of the bargain is as much a fashion statement as the updating of the mobile. Walking through a department store currently is like discovering the aftermath of a hurricane: if it isn’t nailed down, it is for sale. Where does all this discard go ? And we have been manipulated with damnable skill away from what I need to what I want, and want (God Bless Michael Wolff) is the cry of the child. Acquiescence doesn’t necessarily make you happy.

And we have been manipulated with damnable skill away from what I need to what I want, and want (God Bless Michael Wolff) is the cry of the child. Acquiescence doesn’t necessarily make you happy.

Learning to decline was one of the most important lessons of my life. Yes was inevitable, socially agreeable, but looking at something and deciding against it was liberating. There is always pressure to agree, to concur and sometimes to say no is difficult. But then – whoever said life was going to be easy ?